Sigrid Viir “Icelanders Enjoy Living in a Postcard”, 2010. Video, installation. Photography: Reinis Hofmanis

(In)visible Dreams and Streams

An exhibition of Nordic and Baltic Art

Bergs Bazaar, Riga, Latvia 15.09 – 04.10, 2016

Contemporary Art Center in Vilnius, Lithuania 03.12.2016 – 08.01.2017

(Un)comfortable Anniversaries

There is something ‘old-fashioned’ about a noisy birthday celebration; a cliché in the territory of Eastern Europe that is amplified by memories of the demonised Soviet Union’s popular jubilee events, first and foremost annually marking the anniversary of the system with a thematic exhibition flattering the ruling power. In order to dilute the above-mentioned side effects, either irony or a solid institutional backing is employed. Likewise, all fervour and pomp is eradicated, so that the justification for celebrating round or half-round figure anniversaries is strong enough to withstand the scrutiny or the tribunal of contemporary art. Yet, this does not mean, however, that anniversaries are not celebrated: on the contrary, the inclination to hold these kinds of events continues to run strong. At state level, it is precisely culture that is the instrument most frequently used as a format for presenting an institutional report and as a decoration for a party.

Of course, public anniversaries are more often celebrated by organisations with a more traditional bend, such as so-called ‘memory’ institutions. However, excuses for holding major and modest celebrations have also been held by supporters and organisers of Latvian contemporary art events. In 2014, kim? Contemporary Art Centre celebrated its 5th anniversary with an exhibition which was ironically titled The kim? Salon, featuring all the artists who had previously collaborated with them up until then. In 2015, reacting to the new state’s tradition to organise official exhibitions on the anniversaries of major pre-eminent cultural personalities[1], the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art decided to offer an alternative wide-ranging programme of events dedicated to the multimedia artist Hardijs Lediņš[2]. Similarly, in the summer of 2015, the foundation Mākslai Vajag Telpu (MVT – translated as ‘Art Needs a Space’ in English), celebrated the 90th birthday of the classic Latvian painter Džemma Skulme, using shipping containers as exhibition spaces and employing contemporary artists as the producers of the dedication events. MVT also did not neglect the memorial project event format, and so in this year dedications were produced also to mark the passing of Latvian artist and scenographer Ilmārs Blūmbergs (1943 – 2016).[3]

Nordic Strategic Manoeuvres in the Baltic Sea Region

One year before the Soros Foundation started up its activities in Latvia, another institutional and financially significant player appeared in the Baltic states, the Nordic Council of Ministers’ Office, which this year, marked the 25-year anniversary of cooperation between the Nordic and Baltic states with various events including a specially commissioned touring exhibition (In)visible Dreams and Streams. Following the independence of the Baltics States, the Nordic countries’ interests in their restoration and cooperation which followed, can be divided into two phases. The first is linked to the fall of the Iron Curtain in the beginning of the 1990s when the Nordic states – the same as the art operators of Western Europe – began to take an interest in their Eastern European neighbours. The desire to collaborate was demonstrated by invitations to participate in exhibitions, festivals and biennials where, of course, a significant role was played by the Soros Centre for Contemporary Art in the support they provided before this interest soon petered out. The second phase, meanwhile, began in 2009 when the Baltic States were admitted access to the Nordic Mobility Programme (its grants offered support for exchange programmes, visits and residencies) and numerous projects in cooperation with one of the Baltic Sea region countries (Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Iceland, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania or Estonia). It is undeniable that being associated with the circle of Nordic countries bolstered the regional identity of the Baltic States, and additionally promoted the mutual cooperation between both cultural operators.

Over a period of 25 years, offices representing the Nordic Council of Ministers have been strategically placed at several points in the Baltic States, both in the capital cities of Riga, Tallinn and Vilnius, as well as regional centres in the southern and Eastern Estonian towns of Tartu and Narva, where an office was recently opened in February this year. It is most likely because of this that the exhibition organised by the office in Latvia was held in Narva[4], along with Riga and Vilnius, and not in the capital city of Estonia. The choice of exhibition curator was not a coincidence either. Maija Rudovska, an art historian and curator, has extensive experience of working with Nordic countries, both through her participation in residency programmes and the development of many collaborative projects and exhibitions of which her largest project, Society Acts (2014), was on view at the Museum of Modern Art in Malmö. Rudovska has gained experience on both sides of the Mobility Programme; both by having made use of the grant programmes on offer, and by having served as an expert for the Artists’ Residency module of the Nordic Council of Ministers’ Mobility Programme.

(In)visible Dreams and Streams, Bergs Bazaar, Riga. Exhibition view, 2016. Photography: Reinis Hofmanis

Jenna Sutela, Hanna Nilsson “Drop Farm”, 2016. Video. Photography: Reinis Hofmanis

The Dominant Currents or Northern Mainstream

The anniversary exhibition opened in the centre of Riga in its shopping, hotel and restaurant precinct, Berga Bazārs, which is also where the Nordic Council of Ministers’ Office happens to be conveniently situated. The aim of the project was to highlight the results of the Mobility Programme for Culture, accentuating the cooperation networks that had formed over the last decade, whose unobtrusively evident impact could be discerned in the projects carried out by the artists and curators, in addition to the exhibition programmes devised by cultural operators. Out of the 22 participants of the exhibition, a large proportion of the artists, curators, writers and musicians belonged to the generation who are now in their thirties, and have started to become quite active on the artistic scene, after the year 2000. The financial support provided by the Mobility Programme for the purposes of collaboration, travelling and promotion of residencies does, in the long term, undoubtedly leave a positive impact, widening the creative horizon, fostering contacts and offering opportunities for new projects. Likewise, the programme stimulates the development of an internal network within the region, which both in its form and by its participating nations is taking shape to be more hermetic and exclusive by nature. For cultural operators of the Baltic States, for whom domestic funding of culture is the most meagre in the entire region, this status of exclusivity is extremely convenient. On the other hand, for those shaping the cultural life in the Baltic countries, the financial encouragement for the formation of this hermetic cultural environment induces a wish to adapt to their Scandinavian neighbours, in terms of both form and content, the net result of which is that a Baltic Sea Region ‘mainstream’ is developing. In relation to regional neighbours, as once admitted in an interview by the former museum curator of Kiasma and member of the expert panel of the nascent Contemporary Art Museum Collection of Latvia, Mareta Jaukuri, foreign ‘eyes’ seek out the familiar.[5]

Ideationally, the exhibition was built as an interspace where works created in the past could find a home for new projects, and where its site-specific installations could transform in accordance with the venue where they were exhibited. Several works on show in the exhibition marked out the artists’ points of departure for certain developmental phases, a continuation or a conclusion that may have been made possible by the ‘trampoline’ provided by the programme, but it must be added that the project offers only very fragmentary information. The exhibition space also chosen, which previously housed one of the precinct’s offices or shops selling exclusive goods, symbolically represented an interim state between the space of the past and the future. The bare walls and floors – testimony of being in a condition of pre-renovation – is a format that during the lean years of the economic crisis had been seen so many times that, at best, it created associations with the exhibiting policy of the contemporary art festival Survival Kit (its use of an abandoned premises as a social act), or the ‘fast-food’ format exhibitions organised at the disused Tobacco Factory by students in their final year at the Art Academy of Latvia. Unfortunately, this kind of environment lacked suitable lighting making a number of works in look unimpressive causing the total effect to become boring.

The art works on display at the exhibition elicited thoughts about a certain code between Nordic art and its influences on that of the Baltics. The aesthetic language was characterised by romantic minimalism, landscapism and a muted colour palette. Meanwhile the subject matter or content mostly dealt with the relationship between the human being and their surrounding environment, it being with ecologically, politically or intimately and personally charged. This generalised construct, which forms in the viewer’s mind as a clichéd image, was played around with by the Estonian artist Sigrid Virr (1979) in her installation and video work Icelanders Enjoy Living in a Postcard (2010). The artist, herself, could be seen in the video, which attempts to remodel the Icelandic pastoral, shaped by sheep farming, with the planting of fir trees and in this way artificially attempted to reconstruct the desirable advertisement-like landscape.

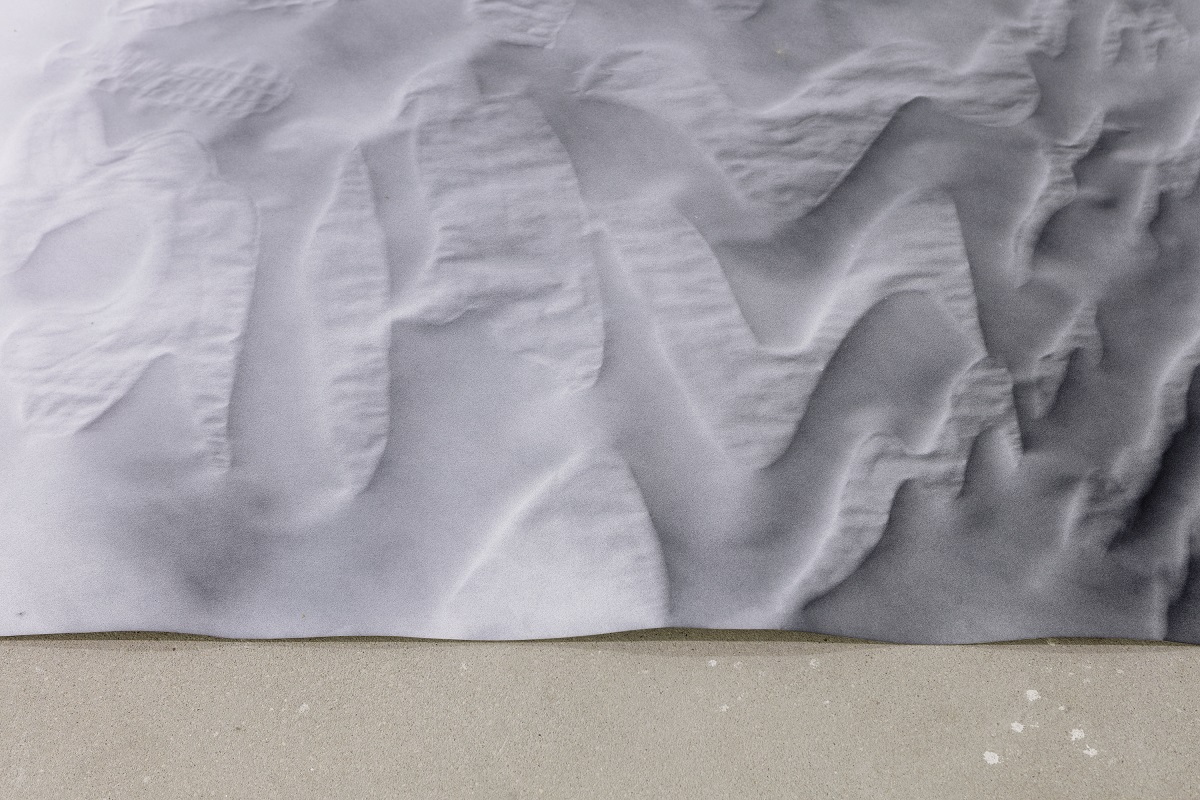

The surrounding ecosystems containing mountains, fjords, volcanoes, forests and marshlands have encoded a certain poeticism in the artists’ projects, which have either directly or indirectly been incorporated into several of the exhibition’s works, both as a hazy, abstract landscape on fragile studio paper in the work Painting on Studio Background (2016) by Finnish artist Maija Luutonen (1978), or in the sliding frames in the work Blind Understanding (2009) by Swedish artist Saskia Holmkvist (1971), that slowly come to reveal the changing riverbed. One of the most romantic works in the exhibition was by the Norwegian artist Sarah Gerats (1983) who in her video series Landscape (..) (2015/2016), integrates herself compositionally into four landscapes before literally merging with the environment around her. Sara’s work can lead one to think about another essential and ever-present spatial category in this language code – that of isolation. In northern Europe, which is far more mountainous and more sparsely populated than the western and southern parts of Europe, the notion of solitude, just like the harsh climate, does not carry with it such profoundly negative connotations. Isolation, escapism, internal dialogue and a confrontation with the existing environment and history could also be perceived in the video work by Latvian artist Ieva Epnere (1977) entitled Four Edges of Pyramides (2015) which placed stories of experiences in the deserted township Pyramide, in the territory of Svalbard, at its centre.

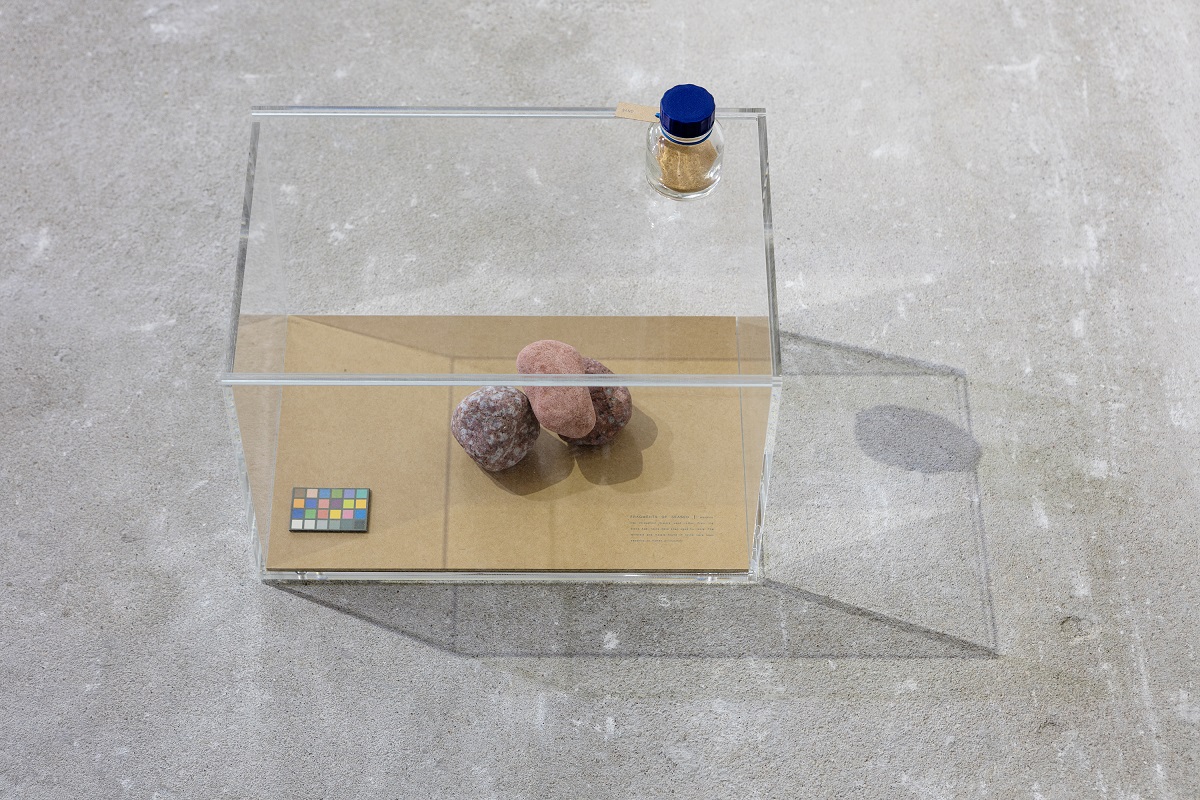

In considering the geographical context, the element that physically unites the Nordic countries and the Baltic States is the Baltic Sea, which was the main theme and focus of examination for Danish artist Lise Haurum (1982) whose work continued her photo series which had been augmented by various other artefacts selected in connection with her research into objects, thus creating an archival showcase type of installation that is continuing to gain popularity. In this context, I wish to mention the work A Carpet, created in 2014 by the Icelandic artist Hildigunnur Birgisdóttir (1980), in which the incorporated painterly motif served both as the reminiscence of a particular popular fashion trend, and also reflected a transformation of the space, the covered floors becoming ornamental meadows. Unfortunately, it was not possible to view this installation at the exhibition, and instead laser cuts of the ornamentations were presented there as sketches instead.

Although the overall tonality of the exhibition was subdued, which is not to say it was grey, but that it was only enlivened by the sunbeams bouncing off the metallic silvery exhibition brochures. One could also have said that the artists’ creative oeuvres enlisted vibrant colour schemes into their palette which has come back into fashion for some time now. Perhaps this is connected with the fact that the features of painting are increasingly being incorporated into spatial installations more often, especially with textiles and ceramics which are two very popular mediums for works of art at the moment. The expert in painterly installations who one could label as ‘the Northern Katherina Grosse’is the Estonian artist Merike Estna (1980), whose big debut was her solo show entitled I’m a Painting (2014) at KUMU in Tallinn. However, not only did Estna present installations at this exhibition, she also exhibited comparatively smallish oil paintings, which were a good size and format for the art market. Another Estonian painter, Mihkel Ilus (1987), is also a participant in the project; he, like Estna, loves to work with colour and spatial structures. This time, however, his 150m long rope installation felt quite expressionless, and its interplay with the space also seemed awkward.

The project also endeavoured to showcase art institutions which undeniably had only to gain from this type of programming which presented opportunities to build up the necessary networks, whilst also offering greater possibilities for collaboration with the artists of the region. To a greater or lesser extent, three institutions were represented at the exhibition: Supernova (LV) – an gallery that formed intensive cooperation links with Nordic countries during its relatively short period of existence, positioning itself as a Nordic satellite in the orbit of Riga; Rupert (LT), an institution that has successfully operated as both an art centre and a venue for residencies; and lastly, the gallery 1857 (NO), which represents artist-initiated project spaces, in this case under the leadership of the Norwegian Steffen Håndlykken (1981). Currently on view at his gallery in Oslo is a group exhibition entitled Curated by a Tre[6], showing work by Ieva Kraule, who co-founded the artist-run gallery 427 (together with Kaspars Groševs).

The programme (re)visiting in Riga has now drawn to a close, though it will be possible to sample this banquet in the format of a Swedish smorgasbord in Vilnius later on in December of this year. Sadly, this exhibition did not really offer an enthralling Nordic odyssey-like adventure with any surprising revelations, which could be linked to several considerations: firstly, the fact that the Nordic Council of Ministers’ Office in Latvia lacks experience in producing exhibitions of contemporary art; secondly, that the exhibition theme was shaped by way of key words like ‘network formation’, ‘transformation’ or ‘identity’, which only served to make it more generalised and overly trendy. Additionally, the bland impression that was left on me by the exhibition might also be connected to what I mentioned earlier at the beginning of this article about the disinclination for jubilee celebrations to be saturated with pomp and emotionality, instead presenting something which resembles more of a visualised accounting report. Despite all of my criticisms at the same time, this project undeniably prompted further reflection on the presence of various institutions, associations and foundations, and the huge importance they have in developing and shaping cultural processes and transformations.

(In)visible Dreams and Streams, Bergs Bazaar, Riga. Exhibition view, 2016. Photography: Reinis Hofmanis

(In)visible Dreams and Streams, Bergs Bazaar, Riga. Exhibition view, 2016. Photography: Reinis Hofmanis

(In)visible Dreams and Streams, Bergs Bazaar, Riga. Exhibition view, 2016. Photography: Reinis Hofmanis

(In)visible Dreams and Streams, Bergs Bazaar, Riga. Exhibition view, 2016. Photography: Reinis Hofmanis

Asdis Sif Gunnarsdottir “Object Perception” 2016. Video, installation. Photography: Reinis Hofmanis

Asdis Sif Gunnarsdottir “Object Perception” 2016. Video, installation. Photography: Reinis Hofmanis

Asdis Sif Gunnarsdottir “Object Perception” 2016. Video, installation. Photography: Reinis Hofmanis

Lise Haurum “The Baltic Sea”, 2016. Installation consisting of photos, objects and text. Photography: Reinis Hofmanis

Lise Haurum “The Baltic Sea”, 2016. Installation consisting of photos, objects and text. Photography: Reinis Hofmanis

Lise Haurum “The Baltic Sea”, 2016. Installation consisting of photos, objects and text. Photography: Reinis Hofmanis

(In)visible Dreams and Streams, Bergs Bazaar, Riga. Exhibition view, 2016. Photography: Reinis Hofmanis

Zane Onckule (Gallery Supernova) “Gallerists”2010/2016. Photography: Reinis Hofmanis

(In)visible Dreams and Streams, Bergs Bazaar, Riga. Exhibition view, 2016. Photography: Reinis Hofmanis

Steffen Håndlykken “Tool Chest”, 2016. Wood, metal. Photography: Reinis Hofmanis

Steffen Håndlykken “Tool Chest”, 2016. Wood, metal. Photography: Reinis Hofmanis

(In)visible Dreams and Streams, Bergs Bazaar, Riga. Exhibition view, 2016. Photography: Reinis Hofmanis

Lars Laumann and Cecilia Lopez “The Wind of Change”, 2016. Audio installation, loop. Photography: Reinis Hofmanis

Maija Luutonen, “Painting on studio background”, 2016. Photography: Reinis Hofmanis

Maija Luutonen, “Painting on studio background”, 2016, detail. Photography: Reinis Hofmanis

Merike Estna, works from the series “everything I have / everything I had / everything I’m going to have / nothing”, 2016. Photography: Reinis Hofmanis

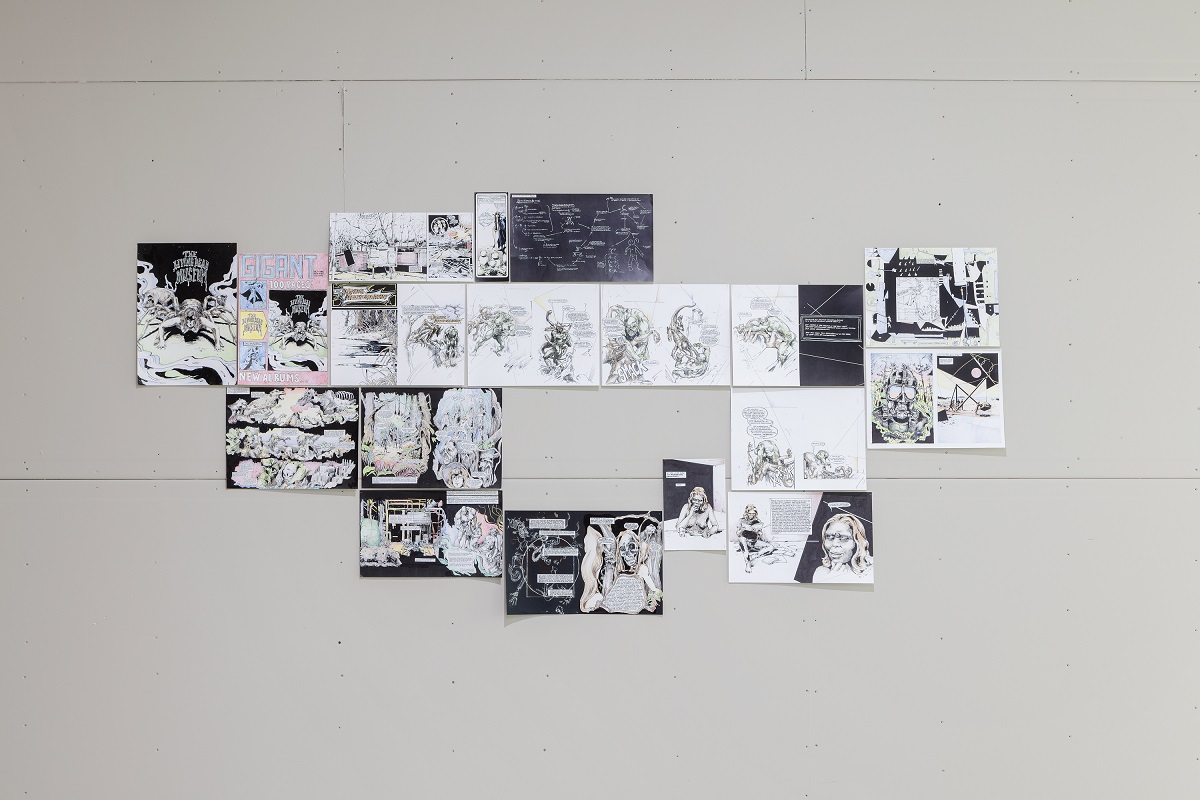

Ylva Vesterlund, excerpts from long forgotten comics, 2016. Photography: Reinis Hofmanis

(In)visible Dreams and Streams, Bergs Bazaar, Riga. Exhibition view, 2016. Photography: Reinis Hofmanis

(In)visible Dreams and Streams, Bergs Bazaar, Riga. Exhibition view, 2016. Photography: Reinis Hofmanis

Hildigunnur Birgisdottir “A Carpet”, 2016 [2014] laser cut cardboard and paint. Photography: Reinis Hofmanis

(In)visible Dreams and Streams, Bergs Bazaar, Riga. Exhibition view, 2016. Photography: Reinis Hofmanis

(In)visible Dreams and Streams, Bergs Bazaar, Riga. Exhibition view, 2016. Photography: Reinis Hofmanis

(In)visible Dreams and Streams, Bergs Bazaar, Riga. Exhibition view, 2016. Photography: Reinis Hofmanis

(In)visible Dreams and Streams, Bergs Bazaar, Riga. Exhibition view, 2016. Photography: Reinis Hofmanis

(In)visible Dreams and Streams, Bergs Bazaar, Riga. Exhibition view, 2016. Photography: Reinis Hofmanis

(In)visible Dreams and Streams, Bergs Bazaar, Riga. Exhibition view, 2016. Photography: Reinis Hofmanis

(In)visible Dreams and Streams, Bergs Bazaar, Riga. 2016. Photography: Reinis Hofmanis

[1] The year 2015 was declared the jubilee year marking 150 years of the classics of literature Rainis and Aspazija, but 2016 has been officially deemed the 150th anniversary year of the classic of Latvian painting, Janis Rozentāls.

[2] To find out more about the year of Hārdijs Lediņš, visit: http://www.lcca.lv/en/the-year-of-hardijs-ledins/

[3] Artists of the first Art Needs Space foundation project Summer House (Vasaras Māja) season series of exhibitions #Džemma 90 (9.06.2016 – 20.09.2015): Arnis Balčus, Darja Meļņikova, Raitis Hrolovičs, Paula Zariņa, Krista Dzudzilo, Kristians Brekte and Indriķis Ģelzis. Curator – Elīna Sproģe. Artists in the second season series of exhibitions #Blumbergs. Bezgalība (9.06.2016 – 11.09.2016): Miķelis Fišers, Ansis Starks, Gints Gabrāns, Voldemārs Johansons, Sabīne Vernere and Andrejs Strokins. Curator – Inga Šteimane.

[4] The exhibition was planned to be in Narva from 15.10.2016 – 20.11.2016, but was cancelled.

[5] From a conversation between Ieva Astahovska and Mareta Jaukuri ‘Jaunie kaimiņi’, Deviņdesmitie, Laikmetīgā māksla Latvijā, Compiler and editor: Ieva Astahovska. – Rīga: Laikmetīgās mākslas centrs, 2010. p.204.

[6] To find out more about the exhibition, visit: http://www.1857.no/1857/exhibits/curated-by-a-tree/53